Ogimi, a serene village nestled on the subtropical island of Okinawa, Japan, is globally recognized as the Village of Longevity. With a population of fewer than 3,000, it's a place where living past 100 is not an anomaly but a common occurrence. What's more remarkable is the vitality, mental clarity, and joy that accompany these long lives.

For decades, researchers involved in the Okinawa Centenarian Study, including Dr. Makoto Suzuki and Dr. Bradley Willcox, have meticulously studied the elders of Ogimi. Their findings challenge many aspects of modern lifestyles. Beyond well-publicized elements like plant-based diets and stress reduction, the true essence of Ogimi's longevity lies in its often-overlooked cultural philosophies.

Here are three crucial lessons gleaned directly from the people of Ogimi, practices that require no expensive supplements or technological interventions, but rather a fundamental shift in mindset, daily habits, and human connection.

The concept of "hara hachi bu," or eating until 80% full, is widely known. However, in Ogimi, it transcends a mere dietary guideline; it's a deeply ingrained ritual of gratitude. Before each meal, villagers recite "Itadakimasu," a phrase expressing humble reception. This mindful moment slows down the pace of life and honors the food, the farmers, and the Earth.

Meals are savored slowly, often served in small dishes emphasizing texture and seasonal colors. Neither food nor life is rushed.

By stopping before feeling completely full, individuals can mitigate insulin spikes, enhance digestion, and reduce inflammation – all critical factors in promoting healthy aging.

Dr. Bradley Willcox emphasizes, "They eat low-calorie, nutrient-dense foods, but it’s their approach to eating that’s so powerful. It’s respectful, balanced, and tied to community.”

One of Ogimi's most treasured traditions is the "moai," a lifelong social network of friends who provide each other with emotional, financial, and spiritual support. Moais are not simply casual acquaintances; they are committed alliances often formed in childhood and nurtured throughout life.

Every villager belongs to a moai, fostering a shared sense of purpose in aging together. From shared meals to communal singing sessions, this support system is an integral part of daily life.

These groups offer more than just companionship. They provide accountability, emotional support, laughter, and protection from loneliness, which research has linked to a higher mortality risk than obesity or smoking.

Dr. Willcox notes, "Social connectedness is their health insurance. That’s why they age so gracefully, with fewer chronic illnesses.”

In Ogimi, nature is not a weekend getaway; it's an integral part of daily existence. Villagers walk daily through verdant hills, pray in sacred groves, and maintain vegetable gardens well into their 90s. Nature isn't merely decoration; it's a guiding force.

The elders don't frequent gyms. Their physical activity stems from climbing steps, tending gardens, and dancing at festivals. Their hands remain in the soil, and their gaze is often fixed on the ocean.

This deep connection to the land fosters patience, rhythm, and acceptance. Seasonal eating and living in sync with the sunrise and sunset align the body’s circadian rhythms, which modern science has linked to improved metabolism and mood regulation.

As one 104-year-old resident shared in a 2015 interview with the Okinawa Times, "In every leaf and root, there’s a rhythm. We just follow it.”

Living like the people of Ogimi doesn't necessitate relocation to Japan. However, it does call for a re-evaluation of the fast-paced, disconnected nature of modern life. Incorporating a few slow meals, cultivating a close circle of trusted friends, and spending more time in green spaces can gently guide the body and mind toward a state of balance.

It's not about doing more, but about acting with intention.

Newer articles

Older articles

Vitamin D Could Slash Tooth Decay Risk by 50%, Study Suggests

Vitamin D Could Slash Tooth Decay Risk by 50%, Study Suggests

Indian Cricket Star Mukesh Kumar and Wife Divya Singh Announce Birth of Son

Indian Cricket Star Mukesh Kumar and Wife Divya Singh Announce Birth of Son

Shubman Gill's Captaincy Under Fire: Bold Calls Needed After England Test Defeat

Shubman Gill's Captaincy Under Fire: Bold Calls Needed After England Test Defeat

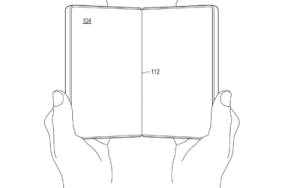

Microsoft Aims for Foldable Redemption with Novel Hinge Design to Rival iPhone and Android

Microsoft Aims for Foldable Redemption with Novel Hinge Design to Rival iPhone and Android

Popular Finance YouTuber's Account Hacked, Bitcoin Scam Promoted: Security Lessons Learned

Popular Finance YouTuber's Account Hacked, Bitcoin Scam Promoted: Security Lessons Learned

Hollywood's Love Affair with India: Iconic Film Locations Revealed

Hollywood's Love Affair with India: Iconic Film Locations Revealed

Esha Gupta Breaks Silence on Hardik Pandya Romance Rumors: 'We Were Just Talking'

Esha Gupta Breaks Silence on Hardik Pandya Romance Rumors: 'We Were Just Talking'

Rishabh Pant Aims to Surpass Virat Kohli in Test Century Tally During England Series

Rishabh Pant Aims to Surpass Virat Kohli in Test Century Tally During England Series

Prithvi Shaw Credits Sachin Tendulkar's Guidance for Career Revival After Setbacks

Prithvi Shaw Credits Sachin Tendulkar's Guidance for Career Revival After Setbacks

Ashada Gupt Navratri 2025: Unveiling Dates, Timings, Significance & Secret Rituals

Ashada Gupt Navratri 2025: Unveiling Dates, Timings, Significance & Secret Rituals